Last weekend I gave a paper at the Resurrecting the Book conference in Birmingham, organised by The Library of Birmingham, Newman University, the Typographic Hub at Birmingham City University and The Library of Lost Books to celebrate the opening of the new public Library of Birmingham in the UK. Underneath some of my notes pertaining to what I thought were the highlights of the conference: Johanna Drucker’s keynote and talks by Hanna Kuusela and Jason Scott Warren.

Last weekend I gave a paper at the Resurrecting the Book conference in Birmingham, organised by The Library of Birmingham, Newman University, the Typographic Hub at Birmingham City University and The Library of Lost Books to celebrate the opening of the new public Library of Birmingham in the UK. Underneath some of my notes pertaining to what I thought were the highlights of the conference: Johanna Drucker’s keynote and talks by Hanna Kuusela and Jason Scott Warren.

Johanna Drucker, in her keynote entitled ‘From boundaries to protocols’, explored various aspects of how we understand the book. She focused on 4 basic areas of investigation, or frameworks, exploring first of all a variety of generative contradictions in how we understand what a book is in bibliography, scholarship, social media and aesthetics. Next to that she explored how the ways in which a book works leads to different sets of ideas of what a book is. Drucker also analysed the question of how the book is being imitated as books turn into ebooks and the variety of distortions and monstrosities this brings with it. And finally, she build upon these generative contradictions to think forward towards the book’s future boundaries and protocols.

In the first part of her talk Drucker elaborates how the book is here to stay. She argues that media do not displace each other in a linear way, where media artefacts exist in ecologies, in systems, where they reconfigure each other. Mentioning Anne Burdick’s ‘The new ecology of things’ research initiative, she explains how media are repurposed according to their media specific affordances and capabilities. There will thus be no media apocalypse for the codex, Drucker argues, where we need to think more critically and synthetically about the development of the book. The question then is, how do we understand what a book is across various different domains, how does it function as an instrument and as an object of inquiry here and what tensions exist in these fields?

In the field of bibliography the focus has been on the development of a critical editing apparatus. The basic tension that exists here is a generative one instead of a binary, which is based on a tension between the codex as fixed, stable and bound and the concept of the fluid text, following the idea that a text is always under transformation. The codex is both a thing and a set of conditions exploring the fluid idiom of the text itself. It is a set of processes and procedures just as much as it is a fixed thing. How do we analyse the different iterations of a text in relationship to the authorative text? And how is this tension muted and how does it change in a digital context?

In the realm of scholarship another tension comes to the fore but it takes a different form here where the fundamental tension is between the nature of argument as a form of synthetic evidence and the way this evidence is put forward in scholarly paratexts. Look for instance at the dialogue with the field and the wider community of research that takes place in the notes and references that accompany a text and how this relates to the construction of the text as someone’s original argument. How is this reflected in the two columns of text that reflect a text’s interior and exterior relationship? What happens in a digital environment when we begin to bring the evidence into the frame of discussion instead of just having pointers towards them in the paratext (in the bibliography, the references etc.)? Here it becomes clear that the book is a fiction that presents itself as a synthetic whole but this notion of the argument having a seamless forward direction is a lie where there is a tension between the synthetic argument and the primary evidence. And it is this primary evidence that is increasingly put forward in digital environments.

The 3rd productive tension exists in the book as a social medium. This is the tension between the insular author and the collective community of discourse. In this sense analogue forms like printed books are like social media in the sense that they are extremely networked and already demonstrate this tension between the individual author and the community of participation surrounding her/him. Drucker mentions Bob Stein’s Social Book experiment as well as her own research surrounding the Ivanhoe project to support collaborative scholarly cooperation as examples that emphasise this tension.

Finally there is a tension in the aesthetic dimension, which is the very useful tension between literal materiality and performative materiality. Drucker mentions the example of Amaranth Borsuk’s and Brad Bouse’s Between page and screen publication in this respect. She emphasises that materiality is always only a provocation for the reading or the performance of the work, for the range of readings that exist. In this sense the performative text makes itself anew in each use where it inverts Mallarmé’s idea of the world absorbed in the book where they actually explode into the world, they explode outward. The main point is thus that we have this useful and generative relationship between material inscription and performative engagement. In this respect, Drucker argues, all reception industry is production industry. As Drucker argues, each of these instances shows the unstable or dynamic notion of the –isness of the book, as being a tense relationship between a concept and an actuality and ideation, which refer to all aspects that have a dynamic relationality.

The second framework that Drucker focuses on with respect to the questions ‘how is a book’, and ‘how is our understanding of it changed’, takes a turn to how a book is made, what are its ergonomics of production and conception? How is body-knowledge linked to conceptual understanding? Here Drucker argues that how you think a book is, is based on how you make a book. The making of the book imprints itself on you. She mentions a few canonical examples to support her argument; William Blake understands the book from the environment of a printmaker’s office, as a printmaker. The book is thus understood in his capacities to make the book. For William Morris his apparatus of production is a printing shop. His conception of the book becomes a whole set of symbolic arguments that are expressed in the making and the production of the book. The Russian Avantgardists’ books are made in domestic environments, on kitchen tables using stencils, staples, newsprints etc. Here the focus is on the glue pot, the scissors, and the group working together. Thinking the book takes place through these forms. As Drucker argues, this is not a technodeterminist idea but it reflects on how conception and production are linked. The book becomes reconceptualised because of its conditions of production. For the activist work’s of the 60s the materials of stencils and the printshop were a central aspect of the circulation of the work, which again in many ways determined the work. And finally there is the example of the Pop Art silkscreens and forms of industrial production which require extended skills and techniques. As Drucker states, how something is made links us all to the systems of labour and the production of value, as well as the economics and politics of production and how they circulate in the production of the codex. The how of the codex informs the is of the codex in radical contextual ways.

The third framework that Drucker introduces is how the book is imitated, what features of the book become the starting points of a remediated form? Why would you remediate the book? In the beginning of the digital era, Drucker argues, the focus was mainly on how to imitate the features of the codex book. The first wave of imitation was thus one of mimicry. This is a ridiculous way of going about rethinking the design of the codex in electronic environments, Drucker argues, where we need to think about its functionalities: what are the set of functionalities that we can transpose? This allows us to distinguish between representation and performativity. These functionalities help us to navigate: what is a page number or an annotation in a digital environment, what is the reading process like? A second aspect of remediation focused on the book as surrogate, as simulacra. Look for instance as the way manuscripts have initially been digitised in online environments. This brought a whole historicity of vision and production with it. Here the focus was not on new-born digital works but on existing works that are presented to you in a digital environment. As Drucker argues, when we fully engage with the networked capabilities of the web, we need to think about how we think and write differently if we work in a digitally structured environment.

At this point Drucker moves to the final point of her talk. How do we move forward towards new protocols and boundaries? Drucker states that the book is a protocol, a set of ongoing conversations between authors and communities, between individuals and documents, between arguments and evidence etc. There is a protocol, a processual aspect behind the book, an aspect that we notice more in the digital environment. In database structures your argument becomes more relational, where the granular components break your argument down and the protocol (i.e. XML) brings it back to the screen. When the content of the work is structured and modular, this makes reuse and repurposing much easier. However, as Drucker argues, you can’t really chunk a scholarly or fictional work in the same way. We do however start to think differently when we are writing in these digital platforms or environments. This leads to different combinatory results, where now you can ‘call it forward’, you can create different screen results, where the combinatory possibilities are only structured by the metadata that are set. With the use of data mining tools, visualisations and displays change, a whole other set of expectations arise. And in this sense the nature of scholarship, of authorship and of display changes too. What does this mean with respect to planning conditional documents? As Drucker argues, we talk about analogue books very differently now that we see them as being way more networked through our work with the web. Next to the fluid text we can now look at the conditional document, which can exist in a set of executed protocols. It is brought into being according to a set of conditions that you have set. But next to that there is a much more extensive condition, one that exists in relationship to the entire web and the relationships that exist there. In this sense there is no delimitation to the domain. The query will have a different result each time the discourse around us changes, which of course changes all the time. The final generative tension thus relates to the nature of a text in an interpretative phase, to its always extensible relationship to the entirety of the human discourse field. In this respect work has a very conditional, momentarily and ephemeral condition. This is one side of this generative tension: the illusion of the infinite production of the text. The delimitation or the boundary is the act of delimitation, the decision to draw a line between what is inside and outside. The fundamental nature of identity depends on this distinction, on this cut. We then understand the book as a boundary condition of textual conditions, as a set of boundary conditions for productions within the infinite world of possibility.

Here we see the tension between protocols and boundaries. The question is then, Drucker argues, how these future imaginations of the text, relate to the generative tensions that have existed historically in the book form. It is no use to distinguish between fixity and distinction, she states. Fixity does not exist, it is an illusion, especially in a scholarly work, and especially when now refreshing work has become very fast on the screen if we compare it to the page. Distinction, Drucker argues, is about an intervention into fluidity to make an intervention, to state ‘here I will make a line’, and this way I create an identity, a boundary condition. This is thus an ontological intervention. Texts and books are contingently ephemeral in a digital condition, because they are always going to change, but without the moment of distinction things don’t have an identity. And this, Drucker concludes, is where we need a fundamental philosophical discussion about.

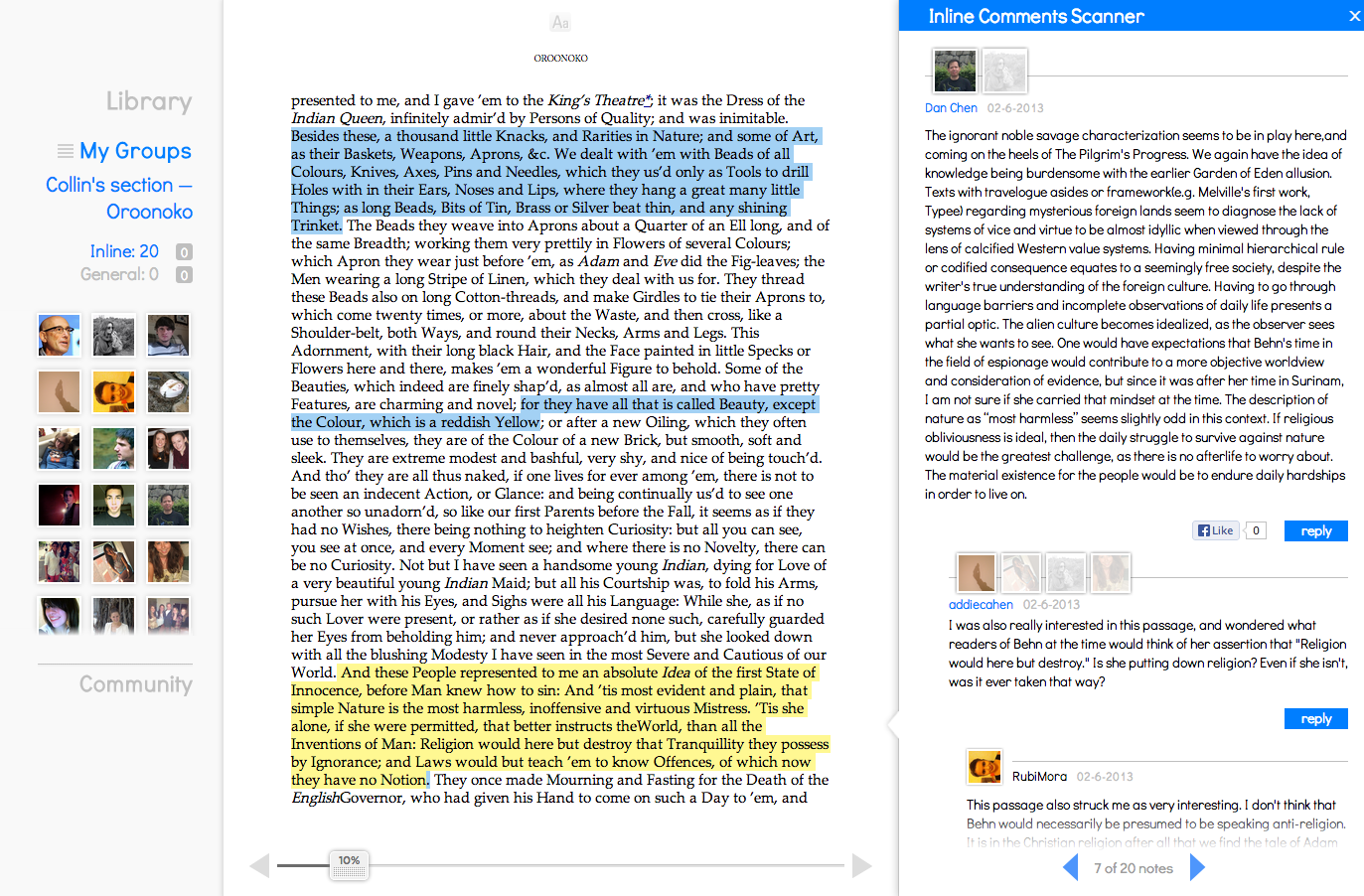

Hanna Kuusela, in her talk on ‘Appropriating books’, explored the role played by readers in literature by looking at their annotations. How do they become agents and what active role as readers do they play in this way? As Kuusela states, readers are taking part in the production of meaning and annotation can be seen as a means of thinking together. Virginia Woolf, Kuusela states, saw annotations as a violence against the author. In this respect there exist dual responses to annotations, where marginalia can also be studied from a historical perspective to find out more about the historical persons doing the annotating. Kuusela however wants to look at practice of annotating in contemporary times, by common readers, thus highlighting the contemporary politics of annotation. She focuses on examples of annotations she has found based on research in her family’s second hand bookstore. From her initial findings she concludes that most books are not annotated that nonfiction books are annotated more than fiction books. Kuusela distinguishes between different forms of annotation: dedications; ownership marks and signatures; highlighter marks; pen and ruler marks; annotations to navigate a text and create order and logic to a text; translations; annotations that serve to build connections and links with other texts and discourses; and annotations that attack the author. As Kuusela states, these are all signs of an active reader, a reader that builds connections. Reading and annotating is thus both a mental idea and a material practice. We are using books to converse with them and to talk back to them. For Kuusela annotation can thus be seen as a form of appropriation. There are different forms of appropriation Kussela states, drawing on Marcus Boon’s distinction in his book ‘In praise of copying’. In the digital age, Kuusela states, readers often feel powerless due to the abundance of texts, which makes it difficult to master them. And then there are all the problems with copyright. Annotating, Kuusela argues, could relativise the power of the author, where the annotating reader has the last word. In this sense it is all about the problem of authority. Annotating introduces a second voice to readers. Kuusela asks, ‘what role are readers given?’ Are they mere consumers, are they objects and targets of cultural institutions or can we give them a more active role? How can we devise strategies of annotation? How can we make the book less of a product in this respect? For this Kuusela draws upon the work of Agamben, seeing appropriation as an act of profanation, as a means to bring the sacred back to the common people. Art is for example one of these sacred things, where appropriation can be seen as a strategy to profane them. The act of touching is important here, the idea of contact, contagion. Signatures and appropriations can then be seen as taking the book away from its god: the author.

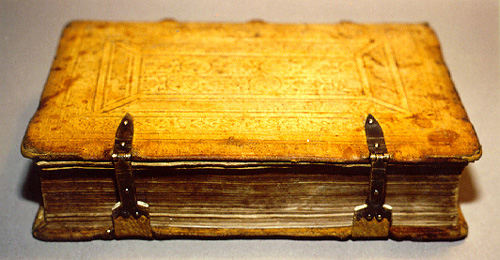

In his talk ‘Ties that bind: on ligatures’, Jason Scott Warren looked at ligatures, not in the typographic sense, but as ‘the act of binding or tying up’ books in the early modern period. As he states, the book was once first and foremost a ligature, a form of connectedness. The book as such has never existed beyond its function of binding disparate things together in many varieties and forms. Thus we should speak of ‘the plurality of different kinds that have taken on the book form’, where the objects themselves are almost categorically distinct. In this sense we don’t have books, he states, we just have book copies. Scott Warren describes ligatures as ‘everything used in binding and tying’. He thus classifies the early modern book as ‘a thing of strings and filaments.’ We know the term ligature from its medical use as bandaging and also in typography, where two or more letters were put together forming amalgamations. This leads to woven fonts, to the interwoven quality of the font. With the shift from handwriting to typography the divorce rate has risen; with the shift in focus to silent reading and evenly spaced letter types a form of alienation also occurs, where the flow of literature has vanished and print has become a form of disembodied writing.

Binding, Scott Warren argues, should be seen as a creative act, where books could be split apart and combined in different ways. Thus it can be seen as a form of cultural binding or appropriation. Through the binding together of new compilations new relationships are established, and rebinding becomes a form of embodied representation. Scott Warren is also interested how this idea of binding as a form of connectedness, as joined up thinking, and similar metaphors, is reflected in the design of books and bindings. He also explored book clasps, which turn each volume into a square, even more emphasised by the box or chest in which books were often kept. Clasps turned books even more into an open or closed thing. Things were now locked in, it symbolises mental darkness, but also the relationship between private and public identity between self and other. And then finally there is the string, of which mostly little survives in old books. This can be seen as a celebration of tactility. Scott Warren sees clear connections here between the textile world of the book and between dressing things up in the world of textile. Ties can thus be seen as a form of foppery, Scott Warren argues. Book ribbons and strings were linked with shoes and ties and clothing. Scott Warren concludes that we should see books in this light, as networks and tissues of material connections.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.